Hands Up! It’s a Fair Cop. I Got Caught Doing 46 in a 40 and Went on a Speed Awareness Course. My Fourth in 35 Years of Driving.

Do speed awareness courses work? I’ll share my own views of this course, the cost, whether I think it achieves behavioural change and what can be done about it.

Pre-Course of the Online Speed Awareness Course

Having paid £100 to have no points and instead to attend an online awareness course, we received our ‘joining instructions’. I can understand that for the training provider and the trainer it’s a tough gig. No attendees want to be there and they all have to attend. No one is there by choice, and they are only accepting the lesser of two evils.

The joining instructions are a lot about having your camera on and being engaged. Reading the many instructions, and watching the videos you get the impression that Drivetech has seen it all before. From ‘my internet broke halfway’, to ‘I can’t turn my camera on because…’, to ‘My dog ate my homework’ and this is drummed into you with a stern – if you don’t do what we say, you can ‘…always take the points laddie’.

Learning Objectives?

As a learning/trainer/training provider the biggest surprise was that there were no learning objectives. No learning outcomes. Even for people not in the world of training, as a Learner, you will have seen learning objectives for the courses you attended. The reason to be. I accept, as a learning provider these are probably more important to us than you. But that said, without learning objectives how will you know what you are here to, well, learn? So, I asked Drivetech and here’s their reply:

‘I just wanted to let you know that in regards to your email about the course tomorrow there are no set lesson objectives as far as I’m aware. The trainer just goes through what they will cover once you are all registered onto the course. It’s just about participation mostly and joining in with conversation and answering anything the trainer asks the group.’

That’s all very nice. Turn up and take part, but what do you want me to have learnt and dare I say, ultimately, what behaviours are you looking for me to change? Slow down. Probably, though if that were the case the learning objective for our negotiation skills training course, would be ‘win more’. If only I’d known it was that easy we would have stopped wasting our time with all these ignorant learning objectives?!

During the Driver Awareness Course

My notes from the course are summarised into 10 points:

Sticky Learning ® is 7 times more effective than 1-day training courses. Plus, you will get a Chain of Evidence proving your Return on Investment. Discover soft skills training that changes behaviours long term.

#1 Be Our Guest

We are called ‘Guests’. Not ‘Learners’. Interestingly McDonald’s calls their customers ‘Guests’ because they believe that they are guests at their restaurants. I’d prefer Drivetech to use ‘Learners’ because at least it reminds us of what we are meant to do – learn.

#2 Mnemonics

The mnemonics are those clever things that trainers use to make stuff stick. Like ‘Naughty Elephant Squirted Water’ to help you learn the points of the compass, as a kid. These were there, in the course, but buried and said too quick to be caught. I did manage to capture a few but then I was looking for them:

-

- ’20 is plenty’.

- ‘Only a fool breaks the 2-second rule’.

- Something about ‘C.O.A.S.T.’ – though it was too quick.

#3 Follow the Structure

The training course structure seemed easy to follow with 4 sections; 1. Know the limit, 2. Know why it matters, 3. Stay in control, and 4. Select a safe speed. It would have been better if the structure had a memorable structure. Like a mnemonic of ‘Road’. The good part of the structure was that they had clearly researched what we need to do, e.g. know the speed limit, know why, etc, but you’d expect that.

#4 Read the Body Language

Looking around at my fellow classmates the body language training I have received over the years was telling me that they were bored. Though I’m not sure any training in body language was needed! They clearly didn’t want to be there. I know this by the chin being propped up by the hand and the far away glazed-over look.

#5 That’s My Name

The trainer’s style was a little of ‘I’ve done this a thousand times’ but you get that in the world of training. Positively, she showed humility and asked people questions by using their names so that no one ‘got away’ without getting involved.

#6 Facts & More Facts

Some of the facts appealed to my blue brain – fact-based brain:

-

- Crashes are most likely to happen in urban areas 62%, rural 33%, and motorways 5%.

- There was a short video about braking distance, but there were too many facts. One takeaway would have been very useful. Maybe something like, ‘+1 mph = 50 feet’.

- 75% of collisions happen at a junction.

#7 New Info

Some new things pricked up my ears:

-

- There’s a Police witness website where you can upload your dashcam footage and the Police will prosecute.

- Some apps can read roadsigns for you.

- ‘Maddygoeselectric’ is supposed to be a great Youtube channel for electric cars.

#8 I Can’t See That!

Some of the images were low resolution. Which is a shame when lots of people will see them and it doesn’t cost much to get a high-resolution image.

#9 Video Over Picture

The variety of animation, video, images, and verbal accompaniment was engaging.

#10 That’s Not a Plan

Towards the end, we completed an ‘action plan’. A paper exercise that starts by asking us why we speed and ends by getting us to answer it and then supposedly we’ve cracked it. Not effective at all.

The course started at around 8.30 am and ended at around 10.45 am.

Others Reviewed the NDORS Course

Trustpilot has 680 reviews with a rating of 4.5 out of 5. The best comment is:

‘I encourage you not to have to go on this course by keeping your speed within the limits. But if you do, know that these guys know their stuff, deliver a great experience, and will teach you things that will you change how you drive permanently.’

And the Worst Comment is:

‘Was referred to this course after being photographed doing 35 in a 30. The first offence in 10+ years of driving. 20,000+ miles a year since 2016. My bad, I totally concede I was at fault. But, I came into the course hoping to learn something and perhaps be a safer driver. Trainer Tony Milton was belittling, sarcastic and petty. Did not foster a positive environment for learning, and seemed more interested in making fun of the course attendees for his own smug pleasure. The only positive is paying £89, taking the morning off work and being treated like a mug for two and half hours is somewhat better than a £100 fine and 3 points. Keep your head down, tell them what they want to hear and finish the “course”.

Bet this is a nice little earner for them! Scum.’

There is a vague inference that Drivetech will monitor your social media and online activity and anything that isn’t good might jeopardise your chances of passing the course. Whether this is the reason for so many positives – no idea. The reviews don’t mention behavioural change but then you’d expect that because the attendees are ‘just’ people and not training providers. Training providers and those in the world of learning are largely looking for changes in behaviour. Our expectations are higher and go way beyond what we call the ‘happy sheet, which is the initial reaction a Learner has to a training course.

The Cost of Speed Awareness and Where it All Goes

The perspective from the ABD on the money taken from speed awareness courses is an interesting one. The Alliance of British Drivers (ABD), is a not-for-profit organisation that is owned and controlled by the mass of road users in the UK.

The ABD wrote an article titled, ‘Where all the money from speed awareness courses went in 2017‘.

The Key Pieces I Took From That Article are:

Money, Money

UK ROED, the company which operates the NDORS driver education scheme, had an income of £61.6 million from fees received, from which £55.9 million was paid to the police. That’s up from £47.5 million paid to the police in the previous year.

Charity

Of the £61.6 million in income, only £1.8 million was paid over to The Road Safety Trust – down from £3.1 million in the previous year). That charity spent £1.3 million on charitable activities which mainly comprise funding for research activities. These are no doubt worthy activities. But the surplus of £485,000 was retained. Thus, this resulted in the assets it held increasing to £4.4 million. In other words, this is not only a charity that does not spend all of its income, but it is also building up a very substantial financial asset figure which is not normally perceived as acceptable for charities.

Where Does it Go?

UK ROED Ltd had £3.8 million of “administrative expenses” but only £764,000 was spent on staff salaries and pensions. It is not obvious where the difference was spent.

£100 Million?

In addition to the £61.6 million that passes through the UK ROED accounts, there are the fees received by the speed awareness course operators. One of the largest course operators is TTC 2000 Ltd whose accounts to December 2017 showed revenue of £26.8 million and profits of £775,000. They run about a third of all speed awareness courses. Therefore, based on that information and the fact that average course fees are about £100, it’s reasonable to estimate that the total fees paid by the 1.2 million drivers attending courses each year is at least £100 million.

No Benefits

Therefore in total, the speed-awareness course system is extracting £100 million from the pockets of road users with no immediate road safety benefit whatsoever and with a trivial proportion (about 1.3%) actually being spent on road safety research or programmes. All the rest goes on expenses including the employment of many ex-police officers.

ABD’s Conclusion?

“Bearing in mind that a recently published report from the Department for Transport (DfT) showed there was no “statistically significant effect on the number or severity of injury collisions” from attendance at a speed awareness course (in other words, NO BENEFIT WHATSOEVER), it is very odd that the Government permits the operations of these companies to continue. It would seem they are self-perpetuating and self-governed organisations that are outside of Government control and which consume £100 million pounds every year of road users’ cash while they have no direct impact on road casualties.

Our Conclusion of the Cost of Speed Awareness and Where it All Goes

£100m is a lot of money and we’d expect to see a benefit. Let’s take a look at this in closer detail…

Evaluating the National Speed Awareness Course

In order to evaluate we need to understand the ‘Impact Evaluation of the National Speed Awareness Course, 111-page report by Ipsos MORI, George Barrett & the Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds. Published in May 2018. ‘Ipsos MORI is a global leader in market research and delivers reliable information and true understanding of Society, Markets and People.’

Click on the image below to see the entire report. The conclusion is shared on pages 31-34, across 3 pages, in section 6:

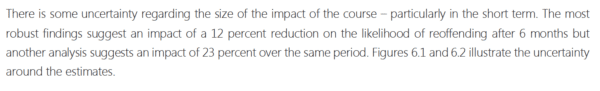

On page 31 a section refers to ‘Reoffending’ and the image shown below is a copy from that section:

Paraphrasing the piece above, ‘…suggests an impact of a 12 per cent reduction on the likelihood of reoffending after 6 months’. £100 million points spent by the road user and all that has been suggested to have been achieved. Not actually achieved, but ‘suggested’, is a 12% reduction.

So, if two people had been found to have been speeding, the only difference between the likelihood of person A and person B reoffending, considering when one went on a course and one didn’t, is a 12% difference. In conclusion, 1.45m drivers attended retraining in 2018. So, 174,000 – our 12 per cent – suggested to have not reoffended. A big number, but what about the 1,276,000 that probably did reoffend!

Surely we can achieve a better outcome with £100m.

Here’s the Even More Curious Thing, According to Auto Express:

‘…But while some police forces send significant numbers of drivers on retraining courses, other constabularies failed to send a single driver on one last year. This trend was highlighted by Steve Gooding, director of motoring research at the RAC Foundation, who said: “What might perplex drivers is how the number of offenders sent on speed awareness courses differs hugely by the constabulary. In 2016, 80,235 drivers were offered the courses in Avon and Somerset and in neighbouring Wiltshire, nobody was.’

Strange. Very strange.

Ok. You Can Find the Problem But What’s the Solution?

The Speed Awareness Course Itself

The trainer, materials, and engagement could be improved. Telling stories, highlighting the mnemonics, sharing great tips, honing in on the facts, better images, etc. But that is not the problem here. If Pareto were to choose he’d say that this is the 20% of the 80:20.

The Model has to Change

The 80% is the model. If we have £100m to spend on designing and delivering an effective speed awareness course then we should spend the money on doing just that – making it effective. That means every Learner is able to complete the survey and say ‘yes it changed my behaviour’.

In the Drivetech 50 question survey, only one question really matters. This one:

It is sent 20-minutes after you complete your course. The fact that it is sent before anyone has had a chance to try anything new is indicative that the training provider is not seeking to achieve behavioural change, but to tick a box, and for that, what a shame.

I can sum up my speed awareness course experience as:

‘Information without application is just entertainment’.

Though it wasn’t really entertaining! So, ‘information…’.

What would a Model Look Like that Works?

There is no silver bullet. Accepted. Though I would be surprised if we couldn’t move the 12 percent dial upwards. Here’s how I would change the model:

- Have learning objectives. The training provider, the trainer and the Learner need to know what they are here to do. Because every effective learning objective around the world starts with ‘By the end of this training course the Learner will know/be able to/…’. For example, if the learning objective was to ‘By the end of this training course the Learner will be able to identify the speed limit on 8 out of 10 roads’. Great, then test each Learner at the end and see whether they can achieve that learning objective.

- Improve the course with stories, mnemonics, etc. as I mentioned above. In essence, improve engagement.

- The key to achieving effectiveness is to incorporate at least one of the learning sciences. Not ignore them all. ‘Spaced repetition‘ is how we all learned to drive (The irony!). One lesson one week, and then another the next week, for about 32 weeks. Changing behaviour over time. I accept that we cannot do 32 lessons of something, though we should also not design a course that is start to finish in one session because it will not change behaviour. Spaced repetition has been around since the 1850s and still, we ignore it.

- Evaluate the training based on Kirkpatricks’ 1953 4-level model. Ask over time, and not immediately after training.

Creating a sticky learning ® speed awareness course may cost a little more. Possibly. Better to spend £150m and achieve 36% than spend £100m and achieve suggested 12%.

The Programme Could Look Like a 10-Part Programme:

- Pre-assessment: Test the Learner on what they know using an animated film. Asking them 3 different sets of questions/scenarios; identifying speed, why and where collisions happen, and braking distances.

- App Data: The Learner downloads an app asking them to submit 3 separate journeys during the programme.

- Virtual Classroom #1: Teach the Learner for 45 minutes about identifying speed with great engagement.

- App Data #1: The Learner submits data of a journey within 1-week of the virtual classroom with a short analysis by them.

- Virtual Classroom #2: Then, teach the Learner for 45 minutes about why & where collisions happen with great engagement.

- App Data #2: The Learner submits data of a journey within 1-week of the virtual classroom with a short analysis by them.

- Virtual Classroom #3: Teach the Learner for 45 minutes about braking distances with great engagement.

- App Data #3: The Learner submits data of a journey within 1-week of the virtual classroom with a short analysis by them.

- Post-assessment: Test the Learner on what they know using an animated film. Asking them 3 different sets of questions; identifying speed, why and where collisions happen, and braking distances. Using different questions/scenarios.

- Evaluation: The Learner completes Kirkpatrick’s 4-level evaluation throughout the programme by answering simple questions on the app. Then, the design of the programme is adjusted based on the evaluation submitted by the Learners, and the data submitted by the Learners.

In Conclusion

We could do so much better by not ignoring the learning science that has been around forever and instead desiring real behavioural change. That said, the ‘institution’ that has created the model would not want it to change because if drivers changed behaviours there would not be the same rate of repeat offenders and therefore not the same rate of revenue coming in each year. So, no one is motivated to deliver change.