The Secret to Spaced Repetition the Ultimate Learning Hack!

You are about to learn how to do spaced repetition, a powerful method that will transform you into a more effective learner. Its effectiveness is based on the retrieval practice effect. Let’s first look at what it does before I explain what it is and how you can profit from it.

What is Spaced Repetition?

The first research into learning and forgetting was in the 19th Century by Hermann Ebbinghaus. Nowadays, he is best known for being the first scientist to uncover the forgetting curve. He taught himself lists of nonsense syllables and then later measured how long it took him to relearn the lists. He spent many months and hundreds of hours doing this. We recently replicated this classic work (Murre and Dros, 2015), obtaining a similar forgetting curve.

Ebbinghaus also explored other aspects of learning and forgetting. In his book ‘On Memory’ from 1885, he wrote that spacing repetitions in time gives superior learning. Since then, scientists have done countless experiments. The outcome is clear. Spacing of repetitions can speed up learning and counteract forgetting. This is true for many types of learning. How to touch type, play the piano, memorise a speech, or to study for school or college. For pretty much any type of learning at all spaced repetition is better. Even for advertising campaigns.

Examples of Spaced Repetition

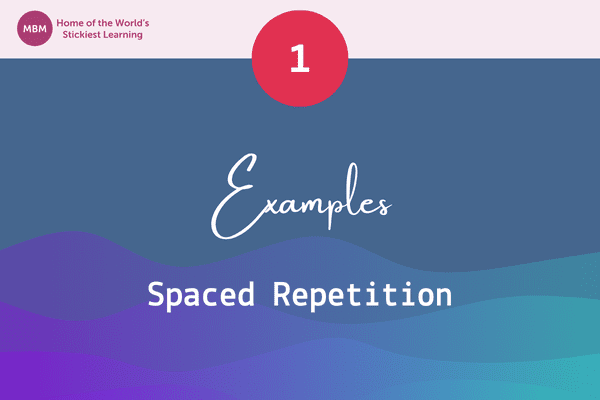

In 1959, Zielske did a classic study into advertising. Over a year, he measured recall of printed advertisements after 13 repeated mailings. He sent the ads to his subjects either every week or every four weeks. The spaced, four-week schedule gave a much higher memory performance.

The figure above shows that recall probability peaked higher in the one-week schedule. However we calculated that total recall was superior using the four-week schedule. All in all, the subjects had a better memory of the products throughout the year (Chessa and Murre, 2007). Also, we demonstrated that with the four-week schedule, forgetting is much slower. Memory for the ads lasted well into the second year.

Another famous example of spaced repetition is a study by Longman and Baddeley (1978). They trained four groups of British postal workers to touch type. They received daily training that varied from 1 hour per day to 2 times 2 hours per day (i.e., 4 hours per day in total).

The 1-hour-a-day group took more days to reach the required level. But they did so in far fewer hours of total practice. So, when you are not in a big hurry to learn something, it is better to distribute practice in time. The reason is that each hour dedicated to learning has more effect.

Benefits of Spaced Repetition

Suppose you are willing to dedicate ten hours to learning a new skill. Then, you can learn more in those ten hours by optimising the spacing of your learning schedule. But how? To answer that, we must first take a closer look at learning processes in the brain.

The brain consists of billions of nerve cells or neurons. Each of these is connected to thousands of other neurons. When we learn something, the neurons fire in a specific pattern. This is short-term memory and, as I show on my YouTube channel (see below), it lasts only 20 seconds.

But if you remain focused on your own thoughts, long-term learning occurs. This happens because a large number of the connections between neurons change in strength. That turns a thought in short-term memory into a long-term memory, which is still there hours or days later.

To realise changes in the connections, it is crucial that neurotransmitters are released in the brain. If that does not occur, the connections do not change, and the memory is not retained. This is the case with the wrong learning techniques. But it may also happen with Alzheimer’s Dementia. This disease destroys brain areas that would normally release neurotransmitters. The lack of these is why Alzheimer’s patients cannot form new long-term memories.

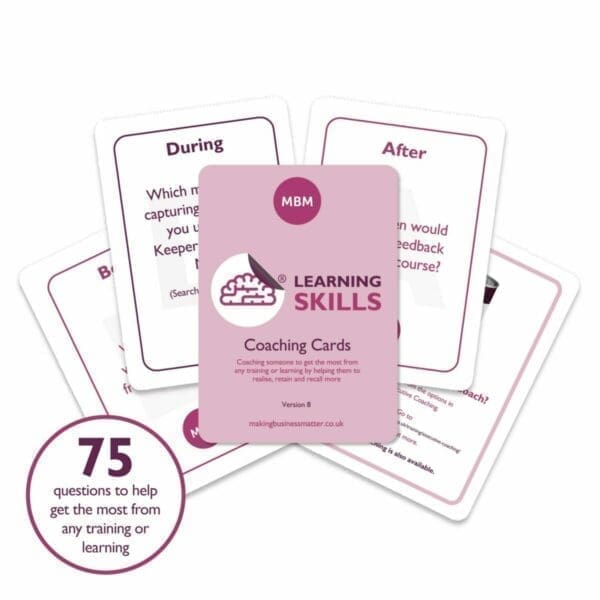

Sticky Learning ® is 7 times more effective than 1-day training courses. Plus, you will get a Chain of Evidence proving your Return on Investment. Discover soft skills training that changes behaviours long term.

Why Massed Learning or ‘Cramming’ Fails

Now we are in a position to better understand the benefits of spaced repetition. The first reason that ‘cramming’ does not work well is that the brain habituates. This is when neural systems say: “We already seem to know this. Let’s not store more of it.”

Research has shown that with new and interesting information, more neurotransmitters are released. But with close repetitions, this is no longer the case. So, even when you are working hard at trying to learn, your brain may tune out on you.

Moreover, cramming also has the danger of making you believe that you have learned something quite well. But as you can see in the left Zielske figure above, you will also forget faster. With cramming you need more time to learn the same amount and you will forget it faster. The only advantage is that for a brief period, you know the material really well.

The Retrieval Practice Effect

The second reason that learning slows down with close repetitions has to do with how the brain responds when you rehearse in an active manner. This is best accomplished by constantly testing yourself. When you do that, the brain responds much better than if you only reread the material.

A question activates the neural systems in the brain, starting a search process for the answer. The learning effect that results from this stimulates learning. When the brain is more engaged like this, again we will observe more neurotransmitter release. And this translates into more changes in more neural connections. As a result, the memory becomes stronger and can more easily be reached when needed.

This is why self-testing is so effective. But there is a caveat: It only works well if you can in fact produce the answer. The superior learning due to testing is the retrieval practice effect I mentioned above. It is key to effective learning.

Spaced Repetition Schedule

We can now determine the optimal spaced repetition schedule. The principle is based on the following simple rule. The best moment to test yourself (to rehearse something) is when you are about to forget it. The reason is that the brain has to work hard to find the answers but can still do it. If you cannot remember the answer, there is much less learning benefit.

Of course, it is hard to know exactly when you will forget something. But it suffices to have a rough estimate. Once you start to pay attention to this in your learning, it is a breeze to find the optimal rehearsal times.

First rehearsals should often be much earlier than people expect. Take for example a high-level skill such as learning a difficult piano piece. With such a difficult task it may be necessary to revise very soon, e.g., only hours after a lesson. In general, when you learn something during the day, the first rehearsal may already be that same evening and not the next day. Methods of rehearsal should always be in the form of tests. Never do ‘mere repetition’ such as rereading the page.

There is an important implication of the retrieval practice effect. Namely, that there is not one schedule that is optimal for everything. If you have a great memory for medical facts, for example, your optimal first rehearsal time may be quite late. A single person will also differ in learning ability for different materials. I am terrible at learning locations and the layout of a new city. But I am quite good with scientific facts. A taxi driver may show the opposite pattern.

The 7-3-2-1 Study Method

So, your first rehearsal session may be quite soon. But the second should be much later. The reason is that your memory will have received a boost from the first repetition. Every next self-test session on the same material will be further and further away in time. This is expanding rehearsal.

An example schedule after an afternoon learning session would be as follows: the same evening, the next day, two days after that, four or more days later, and one or two weeks later.

A variant is the 7-3-2-1 study method where you learn on day 1 and rehearse on days 2, 3, and 7. The 7-3-2-1 method is a good starting point. But be sure to always tailor rehearsal to your learning process. If you notice that you fail most questions of your own self-tests, you waited too long to rehearse. Next time, schedule your rehearsal session earlier. It’s as simple as that.

Spaced Repetition Apps

For learning vocabulary and facts, you can use specialised software. Examples are SuperMemo or Mnemosyne. Many modern language learning apps will also have some form of spacing built in. Most of the existing schedules are built on rather simple assumptions. Some apps, such as SuperMemo, have been developed and adjusted through trial and error. It is possible to calculate optimal schedules mathematically, but this is quite complicated (e.g., Chessa and Murre, 2007). But you now know a simple method to tailor learning schedules to your own needs.

How to Do Spaced Repetition

From now on, test yourself when you are about to forget. Your results will show a dramatic increase. And make sure your learning is as active as possible. With that, I mean test yourself. To help with that, I always tell my students: “Nag your teachers for example exams.” There are two reasons for that: (1) Example questions may help you to test yourself in a more effective manner. (2) They may help you gain a better idea of how to study and what to study. This makes learning even more effective.

YouTube Channel

For more on human memory, visit my YouTube channel.

References

Baddeley, A. D., & Longman, D. J. E. (1978). The influence of length and frequency of training session on the rate of learning to type. Ergonomics, 21, 627-635.

Chessa, A. G., & Murre, J. M. J. (2007). A neurocognitive model of advertisement content and brand name recall. Marketing Science, 26, 130-141.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913/1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology (H. A. Ruger & C. E. Bussenius, Trans.). Teachers College, Columbia University.

Murre, J. M. J., & Dros, J. (2015). Replication and analysis of Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve. Plos One, 10, e0120644.

Zielske, H. A. (1959). The remembering and forgetting of advertising. Journal of Marketing, 23, 239-243